☂️ Intro

When your code includes a suite of unit tests, code coverage is an important metric to measure the test effectiveness and it’s rather easy to obtain; there are plenty of tools around.

Image credits to: Nataliya Vaitkevich

Image credits to: Nataliya Vaitkevich

On the other hand, often we also need to do integration or E2E testing, as in our QA journey we are mostly running real world programs instead of single well-chosen functions.

Let’s start with a basic use case, and prepare a simple program tailored for this purpose.

Suppose we want to test a simple program that prints "Hello, World!" with some optional command line arguments (you can find source code at the bottom 👇):

$ ./hello --help

Usage of ./hello:

-count int

number of times to repeat (default 1)

-header

print also a fancy header

-name string

your name for greeting (default "World")

-upper

convert to uppercase

🚦 Red, Green, Refactor

We are going to use the pytest framework, but any other would work. As a first step, let’s write a failing test:

# test_hello.py

from subprocess import run

def smoke(capfd):

run(["./hello"])

out, err = capfd.readouterr()

assert out == ""

simple run:

$ pytest

============================ test session starts =============================

platform linux -- Python 3.11.11, pytest-8.3.4, pluggy-1.5.0

rootdir: /home/andrea/projects/test

collected 1 item

test_hello.py F [100%]

================================== FAILURES ==================================

_________________________________ test_hello _________________________________

capfd = <_pytest.capture.CaptureFixture object at 0x7f3824e41650>

def test_smoke(capfd):

run(["./hello"])

out, err = capfd.readouterr()

> assert out == ""

E AssertionError: assert 'Hello, World!\n' == ''

E

E + Hello, World!

test_hello.py:6: AssertionError

========================== short test summary info ===========================

FAILED test_hello.py::test_smoke - AssertionError: assert 'Hello, World!\n' == ''

============================= 1 failed in 0.02s ==============================

oh well… We need to assert the right output. Easy peasy:

# test_hello.py

from subprocess import run

def test_smoke(capfd):

run(["./hello"])

out, err = capfd.readouterr()

assert out == "Hello, World!\n"

$ pytest

============================ test session starts =============================

platform linux -- Python 3.11.11, pytest-8.3.4, pluggy-1.5.0

rootdir: /home/andrea/projects/test

collected 1 item

test_hello.py . [100%]

============================= 1 passed in 0.01s ==============================

📣 Say it louder

We are awesome and cool QA Engineers, aren’t we ? 😎 So observing the program command line help, we decide to write a second test, to try out the uppercase feature of our program:

# test_hello.py

from subprocess import run

def test_smoke(capfd):

run(["./hello"])

out, err = capfd.readouterr()

assert out == "Hello, World!\n"

def test_uppercase(capfd):

run(["./hello", "-upper"])

out, err = capfd.readouterr()

assert out == "HELLO, WORLD!\n"

$ pytest

============================== test session starts ===============================

platform linux -- Python 3.11.11, pytest-8.3.4, pluggy-1.5.0

rootdir: /home/andrea/projects/test

collected 2 items

test_hello.py .. [100%]

=============================== 2 passed in 0.02s ================================

🎉 🎉 We doubled the test coverage, celebrate! 🎉 🎉 Our job seems done …

Wait … Actually, how can you say when our tests are good enough ? How much of the program code are you actually running ? Do our tests avoid or miss some key feature ?

🌡️ Bring in the meter

For each test run, we need to measure the ratio between the code executed and the total code in the program. This is a tricky subject and mostly it depends on how the program is built, but as a first step we can use a feature that Go has introduced a couple of years ago, starting from version 1.20.

So, let’s rebuild the program with coverage informations in the binary:

$ go build -cover hello.go

Once compiled, the program gives us an hint on something changed:

$ ./hello

warning: GOCOVERDIR not set, no coverage data emitted

Hello, World!

The Go compiler instrumented the program, and now we need to give it a path where to store the collected coverage data. So, lets’ prepare a simple script that will setup the environment and also run our test suite:

$ cat cov_test.sh

#!/bin/sh

rm -rf covdatafiles

mkdir covdatafiles

rm hello && go build -cover hello.go

GOCOVERDIR=covdatafiles pytest

The run is apparently not changed:

$ ./cov_test.sh

============================== test session starts ===============================

platform linux -- Python 3.11.11, pytest-8.3.4, pluggy-1.5.0

rootdir: /home/andrea/projects/test

collected 2 items

test_hello.py .. [100%]

=============================== 2 passed in 0.02s ================================

but now we have some data in a new subfolder:

$ ls covdatafiles

covcounters.6d07efc23254e1696fe8a1428981e28e.13877.1740324625565161919

covcounters.6d07efc23254e1696fe8a1428981e28e.13882.1740324625569223562

covmeta.6d07efc23254e1696fe8a1428981e28e

these files are intended to be processed by another tool:

$ go tool covdata percent -i covdatafiles

command-line-arguments coverage: 85.7% of statements

🐤 Another baby step

let’s add another test and see if our coverage increases:

from subprocess import run

def test_smoke(capfd):

run(["./hello"])

out, err = capfd.readouterr()

assert out == "Hello, World!\n"

def test_uppercase(capfd):

run(["./hello", "-upper"])

out, err = capfd.readouterr()

assert out == "HELLO, WORLD!\n"

def test_header(capfd):

run(["./hello", "-header"])

out, err = capfd.readouterr()

assert out == "-------------\nHello, World!\n"

🚀 Hooray !

$ go tool covdata percent -i covdatafiles

command-line-arguments coverage: 92.9% of statements

We did a step forward, and we can safely claim our tests are better than before.

Since we are at it, let’s integrate the coverage output into our test script:

$ cat cov_test.sh

#!/bin/sh

rm -rf covdatafiles

mkdir covdatafiles

rm hello && go build -cover hello.go

GOCOVERDIR=covdatafiles pytest

go tool covdata percent -i covdatafiles

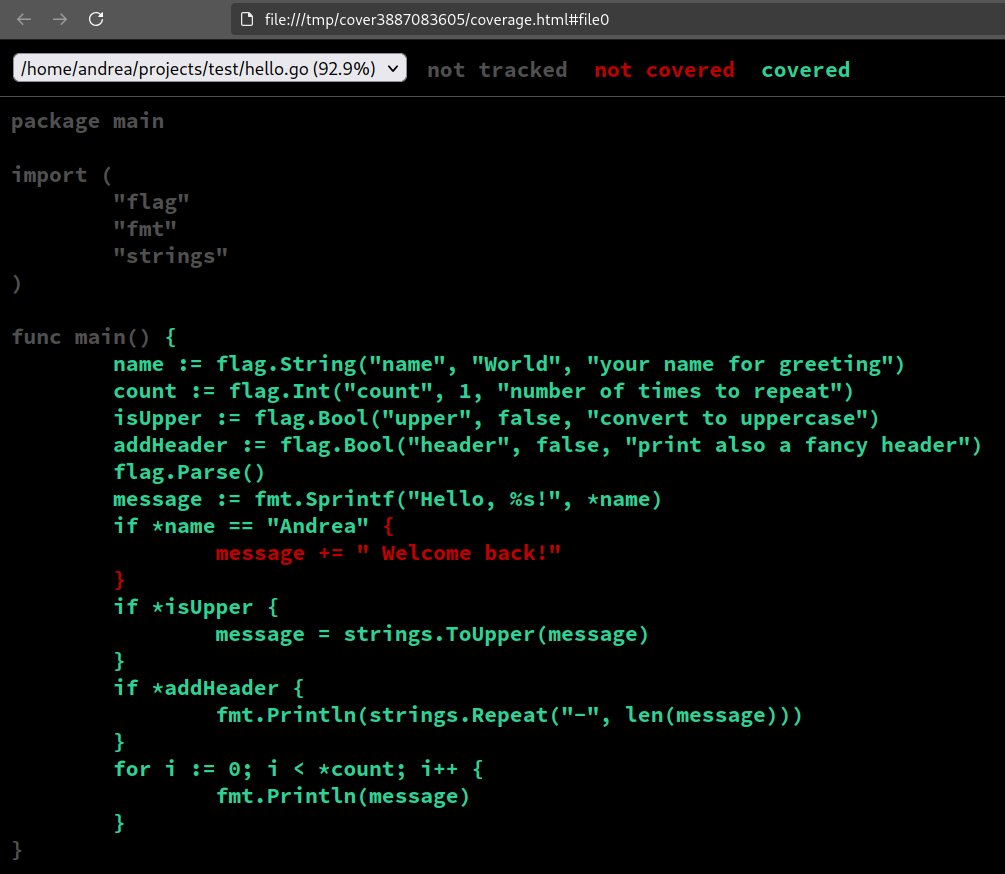

🔎 Use the source, Luke

Now a question for the reader; looking at the source code of the program:

package main

import (

"flag"

"fmt"

"strings"

)

func main() {

name := flag.String("name", "World", "your name for greeting")

count := flag.Int("count", 1, "number of times to repeat")

isUpper := flag.Bool("upper", false, "convert to uppercase")

addHeader := flag.Bool("header", false, "print also a fancy header")

flag.Parse()

message := fmt.Sprintf("Hello, %s!", *name)

if *name == "Andrea" {

message += " Welcome back!"

}

if *isUpper {

message = strings.ToUpper(message)

}

if *addHeader {

fmt.Println(strings.Repeat("-", len(message)))

}

for i := 0; i < *count; i++ {

fmt.Println(message)

}

}can you think of one last test we can write to reach 100% coverage ? 😉

Good news: we can have a visual hint by producing an html output! We just need to add a couple more lines of post-processing:

$ go tool covdata textfmt -i=covdatafiles -o=coverage.txt

$ go tool cover -html coverage.txt

Oh yes, now it’s very clear what we are missing 😄

def test_andrea(capfd):

run(["./hello","-name","Andrea"])

out, err = capfd.readouterr()

assert out == "Hello, Andrea! Welcome back!\n"

🧪 Final words

Thanks to the excellent Go tooling, adding coverage information to compiled binaries is straightforward and we can finally have an idea on how much code our tests are probing.

I’m sure it’s a very important metric to have, so we can think about some ways to expand this concept to other languages and technologies.

update: there is a follow up post, you can read it here

Feel free to leave me comments and feedback, happy hacking! 👋